by José Igreja Matos, President of the European Association of Judges

▪

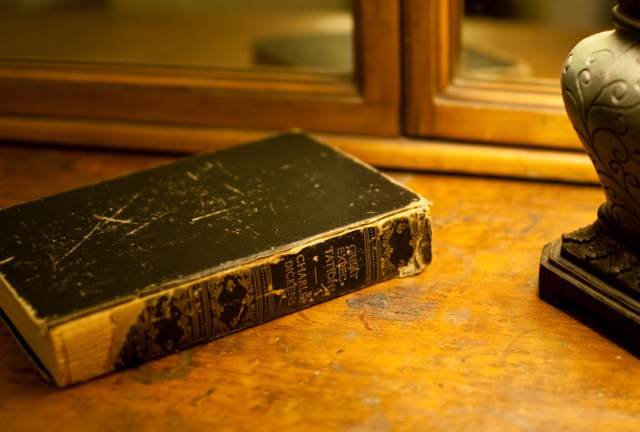

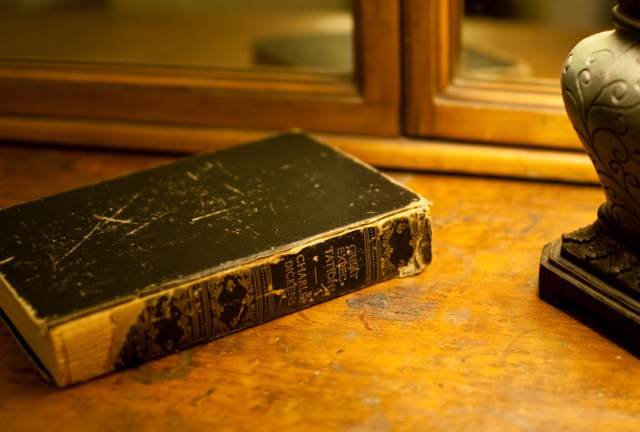

“In the little world in which children have their existence”, says Pip in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations, “there is nothing so finely perceived and finely felt, as injustice.” (…) But the strong perception of manifest injustice applies to adult human beings as well. What moves us, reasonably enough is not the realization that the world falls short of being completely just – which few of us expect – but that there are clearly remediable injustices around us which we want to eliminate.” – Amartya Sen, “The idea of Justice” (preface).

As V. Skouris [former President of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)] brilliantly explained in his speech at the conference Assises de la Justice (November 21, 2013), when analysing matters related to judicial independence, there is a traditional distinction between personal independence and substantive or functional independence. The former essentially refers to the personal qualities of the judge and is destined to ensure that in the discharge of his or her judicial function, a judge is subject to nothing but the law and the command of his or her conscience. The latter of this is the functional independence which refers also to the judicial institution as a whole; it means that the terms and conditions of judicial service are adequately secured by law so as to ensure that individual judges are not subject to any executive control. Judicial independence within the European Union legal order concerns not only the CJEU but also national courts at all levels, since national judges are also what we call in French “juges de l’Union du droit commun“.

Unfortunately, the situation in Turkey is characterized by an affront towards basic standards of judicial independence. Turkey was one of the first countries, in 1959, to seek close cooperation with the then very recent European Economic Community. This cooperation was realised in the framework of an “Association Agreement”, known as the Ankara Agreement, which was signed on September 12, 1963. The CJUE was already called to focus precisely on this Association Agreement for instance in relation to the issue of their limits (Judgement Dereci and others v Bundesministerium für Inneres, Case C-256/11, EU: C:2011:734). This associative status implies that European Union naturally concerns about matters involving Turkey, and what happens with the Turkish citizens concerns the EU citizens. However, the idea “a judge is subject to nothing but the law and the command of his or her conscience” – to use the language of V. Skouris – is today completely marginalized in Turkey as pointed out by different European entities. Some concrete examples can be provided in this regard:

I) In December 8, 2016 the European Network of Councils of Judiciary (ENCJ) decided, in General Assembly, to suspend, with no Council voting against, the observer status of the Turkish Judicial Council (HSYK). Thus the HSYK is now excluded from participation in ENCJ activities. The reasoning of the ENCJ was impressive: “it is a condition of membership, and for the status of observer, that institutions are independent of the executive and legislature and ensure the final responsibility for the support of the judiciary in the independent delivery of justice. (…) taking into account the failure of the HSYK to satisfy the ENCJ that its standards have been complied with, the statements of the HSYK, as well as information from other sources including the reports and statements of the European Parliament, the European Commission, the Human Rights Commissioner of the Council of Europe and Human Rights Watch and the Venice Commission, the ENCJ decided that the actions and decisions of the HSYK, and therefore the HSYK as an institution cannot be seen to be in compliance with European Standards for Councils for the Judiciary. Therefore, the HSYK does not currently comply with the ENCJ Statutes and is no longer an institution which is independent of the executive and legislature ensuring the final responsibility for the support of the judiciary in the independent delivery of justice.” Security of tenure of office is a core element of the independence of a judge and the dismissal of judges should be used only in case of misuse of the exercise of office (e.g. UN Basic principles on the Independence of Judiciary, Opinion para 95, 92, 63, Rec para 49 and 50). However, HSYK adopted a decision with only 62 pages of reasoning sufficient to dismiss thousands of judges. The decision is totally inadequate when the criminal investigations used as motive to sack those judges are still in a pre-trial stage; the principle of the presumption of innocence, which is enshrined in Article 5 of the European Convention for Human Rights (ECHR), was consequently completely ignored, if not violated.

Continue reading “European Union and Turkey: judicial independence at a crossroads” →